19th Century New Orleans Photography

The Creation of Visual Immortality

In the months

following Louisiana's secession from the Union, scores of military units were

formed in the state of Louisiana. Most volunteers traveled to the New Orleans

area to be mustered into Confederate service. While there, several New Orleans

photographers recorded their images. Some local photographers even

departed with the troops, trading their cameras for arms. Theodore Lilienthal

joined the Washington Artillery; A. Constant, the Orleans Guard; Warren Cohen,

the Crescent Regiment; William Guay, the Louisiana State Militia; Bernard and

Gustave Moses, the 21st Louisiana Infantry; Samuel Moses, the 11th

Louisiana Infantry; Louis Prince, the 2nd Louisiana Cavalry, and

finally John Clark, a purser in the Confederate army. And a few of these artists

actually took to the field to capture their images: Mrs. E. Beachbard, the only

known local female photographer of the time, died of disease while photographing

Confederates at Camp Moore; J. W. Petty photographed the Washington Artillery

while in camp in New Orleans; and J. D. Edwards photographed Confederate

soldiers in camp and drill in Pensacola, Mobile, and Virginia.

Ambrotype of female Confederate photographer Mrs. E. Beachbard taken at Camp Moore of Mississippi soldier Edward Lilley. It is

attributed to her by her signature use of image identification. This image is

marked, “ Edward Lilley /Camp Moore/ July 5th 1861.”

Ironically,

all of these Confederate photographers owed their trade to a black man. Portrait

painter Jules Lion was the first in New Orleans to show the invention of

photographic art, the daguerreotype, in 1840. He was a “free man of color.” He

had learned the process in 1839 while visiting Paris, hometown of its inventor,

Louis Daguerre. The daguerreotype, commonly called a “dag,” was an image formed

on a polished, silvered copper plate made light sensitive by its exposure to

vapors of various chemicals. The resultant image was a “direct” image, and thus

the subject appeared to the viewer in reverse. Although there are no known Lion-

labeled images of Confederates, Lion was well-known for photographing New

Orleans’ most distinguished citizens: clergymen, judges, attorneys and members

of the military. Lion did sign one lithograph of famous composer Harry Macarthy

as a Confederate soldier used for his patriotic sheet music, which was published

by A. E. Blackmar of New Orleans in 1861.

Jules Lion

lithograph of Macarthy

Jules Lion drew the illustrated image of the famous composer

Harry Macarthy with his wife Lottie Estelle on the cover of this

patriotic Confederate sheet music, which included his famous composition The

Bonnie Blue Flag. Lion’s likeness of Macarthy is only one of three known to

exist-none of them photographs.

The art of

photography advanced during the antebellum years, and by the time Louisiana

joined the Confederacy a newer process replaced that of the daguerreotype. Early

Civil War photography was captured on ambrotypes (meaning “immortal pictures”),

glass plates with light-sensitive collodion that created negative images on

their reverse sides. James Cutting of Boston and his partner, Isaac Rehn of

Philadelphia, had developed this process in the mid-1850s. It proved to be a far

superior product to the daguerreotype due to its cheaper cost and faster

exposure time. Development of the photographic process continued into late 1861

when Professor Hamilton Smith of Ohio invented a yet newer process in which

negative images were formed on thin sheets of tin. These images were called

ferrotypes, or “tintypes.” These tintypes proved much more durable than their

glass counterparts, and lowered the cost of photography even further, allowing

almost all soldiers the opportunity to capture their image for their loved ones

prior to going off to war.

New Orleans photographers quickly adapted to the lucrative

business of taking photographs of military soldiers. This ambrotype taken by

Washburn & Co. of New Orleans captured an example of a unique social status in

antebellum New Orleans. These Confederate soldiers are half brothers, the one on

the right a mulatto.

However, the

most common photographic process used during the Civil War was the use of a

glass negative to expose a paper coated with egg white, which created a paper

positive called an albumen. This form of photography could be mass produced and

included the very popular small carte-de-visite (calling card), commonly called

a “cdv.” Cdvs were handed out as calling cards and collected by many citizens as

souvenirs of their cherished famous leaders.

CDV of Washington Artillerist

Civil War

images were produced in various sizes. The larger the size, the higher the cost.

A full photographic plate, whether an ambrotype or tintype, measured 6 1/2 by 8

1/2 inches, a half plate 4 1/2 by 5 1/2, a fourth plate 3 1/4 by 4 1/4, a sixth

plate 2 3/4 by 3 1/4, and a ninth plate 2 by 2 1/2. The most commonly purchased

“hard” image was the sixth plate. Cardstock cdvs, or “soft” images, measured 2

1/2 by 4 inches.

Affluent

Washington Artillery members could easily afford to have their images taken as

mementos for family and loved ones prior to leaving the city. In fact, they

could also afford to have group photographs taken while in camp. J. W. Petty of

156 Poydras Street is the only New Orleans photographer with documented outdoor

albumen images of the 5th Company Washington Artillery while its members were

stationed at Camp Lewis (now Audubon Park). Several of the photos bear his name

and address on their card stock. Although other images do not bear his mark,

Theodore Lilienthal may have taken others, since Lilienthal had joined the

Washington Artillery’s 6th Company and was in New Orleans when the

photographs were taken in 1862. J. D. Edwards has also been credited for some of

these outdoor images.

5th Company,

Washington Artillery in the field -Camp Lewis

(now Audubon Park)

Sign reads,

"No. 2/ 64 Carondelet St."

Note striped

tent, reported to have been made from circus tent canvas.

However,

there is little doubt that Jay Dearborn Edwards pioneered the use of outdoor

photography during the Civil War. When other photographers were satisfied with

traditional studio art, Edwards was carrying his equipment over rugged terrain

to capture scenes of Confederate soldiers in camp and within Southern forts.

Although he sold these images to the New Orleans market, the more prolific and

famous northern photographers Brady and Gardner later overshadowed his talents.

It was not until after the war that his innovative genius was recognized. When

Francis Miller started his search for Civil War photographs for his

monumental 1911 ten volume Photographic History of the Civil War, he sent

a researcher to New Orleans to search for Confederate images. The researcher

called upon the Washington Artillery Arsenal in New Orleans. Its one-armed

armorer, Sergeant Dan Kelly, “said that there were no photographs, but consented

to look in the long rows of dusty shelves which line the sides of the huge, dark

armory. From almost the last he drew forth a pile of soggy, limp cardboard,

covered with the grime of years. He passed his sleeve carelessly over the first,

and there spread into view a picture of his father sitting reading among his

comrades in Camp Louisiana 49 years before. The photographs were those of J. D.

Edwards, who had also worked at Pensacola and Mobile. Here were Confederate

volunteers of ’61 and the boys of the Washington Artillery which became so

famous in the service of the Army of Northern Virginia.” [Camp Louisiana was located near Mitchell’s Ford on Bull Run

River northeast of Manassas Railroad Junction in Northern Virginia, July 8,

1861.] Today, these outdoor albumen scenes and cartes-de-visite can be used to

help determine some historical facts about their subjects.

Glove

of Dan Kelly-veteran & armorer of Washington Artillery Arsenal.

Many

photographers placed advertisements on the front or back of their carte-de-visite

stocks, the latter called a “back mark,” which can now be used to help date the

image. Back marks identified the photographer by name, address, and city. Since

many New Orleans photographers moved from studio to studio, their addresses can

be cross-referenced with old annual city directories to determine the era of the

image.

Advertisements not only appeared on the back of cdvs, but by the

use of tokens and business cards. Here is an example of a token from the

daguerreotype studio of E. Jacobs and a business card from J. W. Petty.

For example,

many images of Washington Artillerists were taken by Samuel Anderson and Samuel

T. Blessing, partners in photography, whose 1861 address was 61 Camp Street. By

1864 the two photographers dissolved their partnership and by 1865, after the

war, Anderson merged with Union photographer Austin A. Turner of New York.

Therefore, by merely viewing the back mark on the reverse of a cdv card, one may

determine when the image was sold.

Many

Washington Artillery cdvs also exhibit a postage stamp affixed to their reverse

sides. The stamp represents payment of a photographic tax levied on the sale of

images in late 1864. The rate of taxation was determined by the cost of the

image. Standard cartes-de-visite, without coloring or touchups that sold for

twenty-five cents, required two-cent postage stamp(s) or “revenue” stamps) to

be placed on the reverse of the card. The stamp(s) were “cancelled” by the

penned initials of the photographer. Therefore, any cdv with a revenue stamp

automatically dates it’s sale to the late war, if the subject is Union, or the

immediate post war era if Confederate, since loyal Confederates did not start

reentering the city until May of 1865.

Reverse of

Washington Artillerists' cdvs

with "backmarks,"

revenue stamp, & signature (Anderson &

Turner/ New Orleans)

(Note: One cannot

always be sure that the image was taken

at the date noted by the backmark address on the reverse. A subject may have posed for

his photograph at an earlier date

and his image kept on file as a glass “negative” and additional copies printed

later.)

William Watson Washburn's Studio on Canal St.

Louis Prince's Photographic Studio on Canal St.

By 1866 the revenue stamp was no longer

required, and the cdv started to fall out of favor to the much larger “cabinet

card” image.

Larger cabinet card of Robert & Beauregard Whann of the Washington Artillery-

circa 1880s

If a back

mark is not present on a cdv, other clues may help identify a particular

photographer. Many photographers used “signature” props in their photographs. It

was quite common to see these same studio props, i.e. a fancy chair or drape,

from one Washington Artillery portrait image to another. In some images,

multiple variations of these props were used. A studio’s signature linoleum

flooring or painted backdrop can also be used to help identify the photographer. Personalized

cdvs can also help date or identify an image. Often the pictured soldier would

personalize the reverse of a cdv by adding a signature or an inscription with

the date when the image was taken. Finally, a

subject’s clothing can help date the photograph. After the Civil War, it was a

crime for Confederate veterans to be photographed armed or in full uniform.

(Confederate veterans could not bear arms.) Because of this ban, members of the

Washington Artillery are often seen in post war Anderson & Turner

cartes-de-visite wearing civilian clothing, or their Confederate shell jackets

or frock coats but wearing white, summer dress nonmilitary pants and no

accoutrements. Often, the photographer would also blacken out the military

buttons on their Confederate frock coats. One famous example of this ban is

photographer Miley’s post war image of Robert E. Lee on his horse Traveller. Lee

is seen in uniform without his military insignia or sword.

Several

favorite New Orleans photographers and their wartime carte-de-visite back mark

addresses include:

Samuel

Anderson 61 Camp St. 1860-1864

E.

Beachbard 173 Rampart St. 1861

Camp Moore, La. 1861

Samuel T.

Blessing 61 Camp St. 1860-1863

Anderson &

Turner 61 Camp St. 1864-1865

John H.

Clark 101 Canal St. 1861-1865

A.

Constant 20-21 Hospital St. 1861-1865

A. Constant &

L. Moses 21 Hospital St. 1866

Jay Dearborn

Edwards 19 Royal St. 1861

William M.

Guay 108 Poydras St. 1861-1862

75 Camp St. 1863-1864

Edward

Jacobs 93 Camp St. 1860-1864

Theodore

Lilienthal 102 Poydras St. 1862-1865

Felix

Moissenet 6 Camp St. 1861

Bernard

Moses 46 Camp St. 1861-1864

Gustave

Moses 46 Camp St. 1861-1865

Samuel

Moses Camp & Poydras 1861-1865

J. W.

Petty 136 Poydras St. 1861-1865

Louis Isaac

Prince 112 Canal St. 1861

8 St. Charles St.

1865

William

Watson Washburn 142 Canal St. 1861-1865

113 Canal St. 1866

Without the

proliferation of these Southern photographers and the survival of their historic

photographs, the story of America’s Civil War would not have the same impact on

today’s generation. They imprint upon the viewer’s mind an eternal, fixed image

to a name or event. These images help make those heroic Civil War soldiers

immortal.

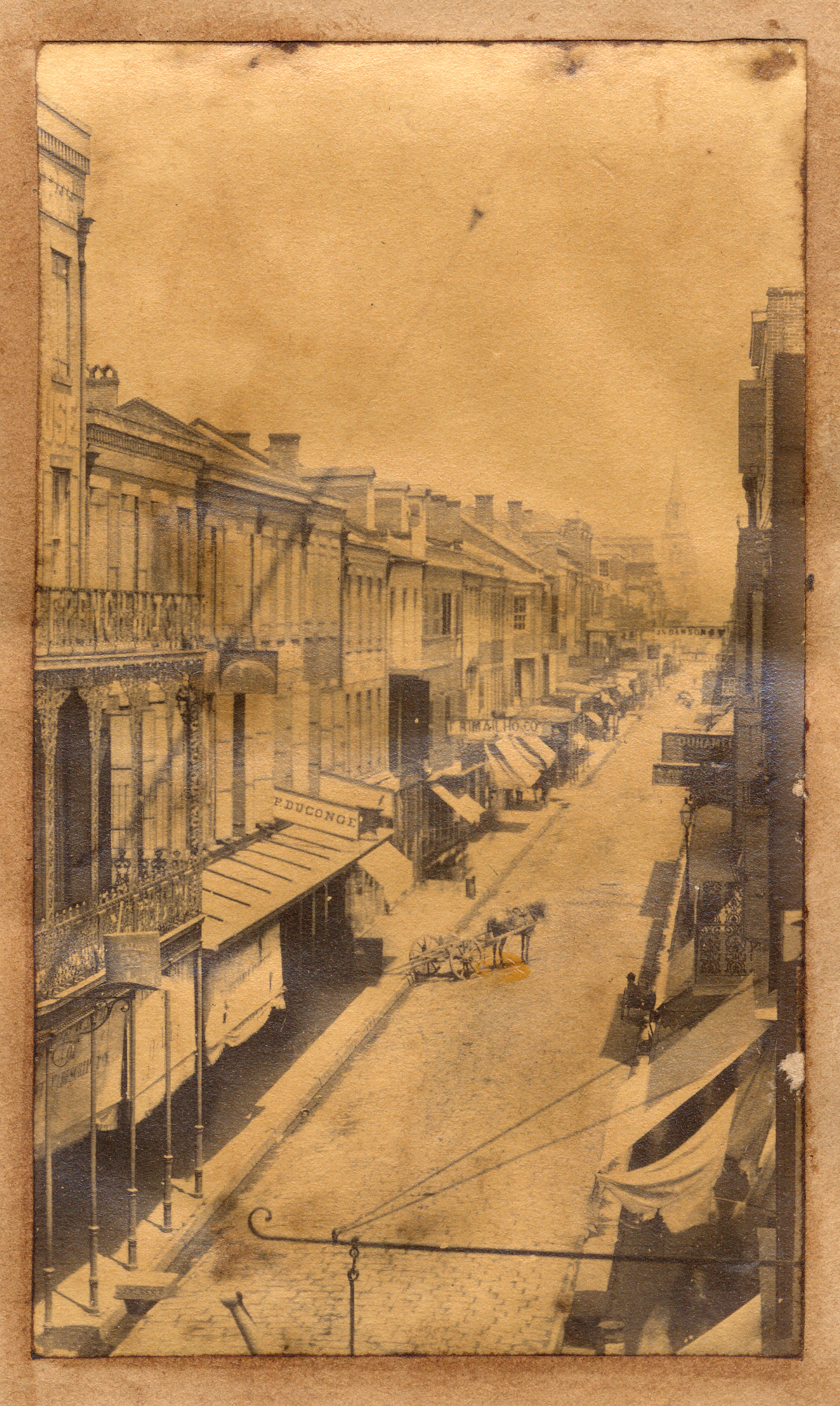

New Orleans

Through the Eyes

of Its Photographers

Jackson Square and the French Quarter

as seen from the east bank across the levee near Bienville St. on the

riverfront.

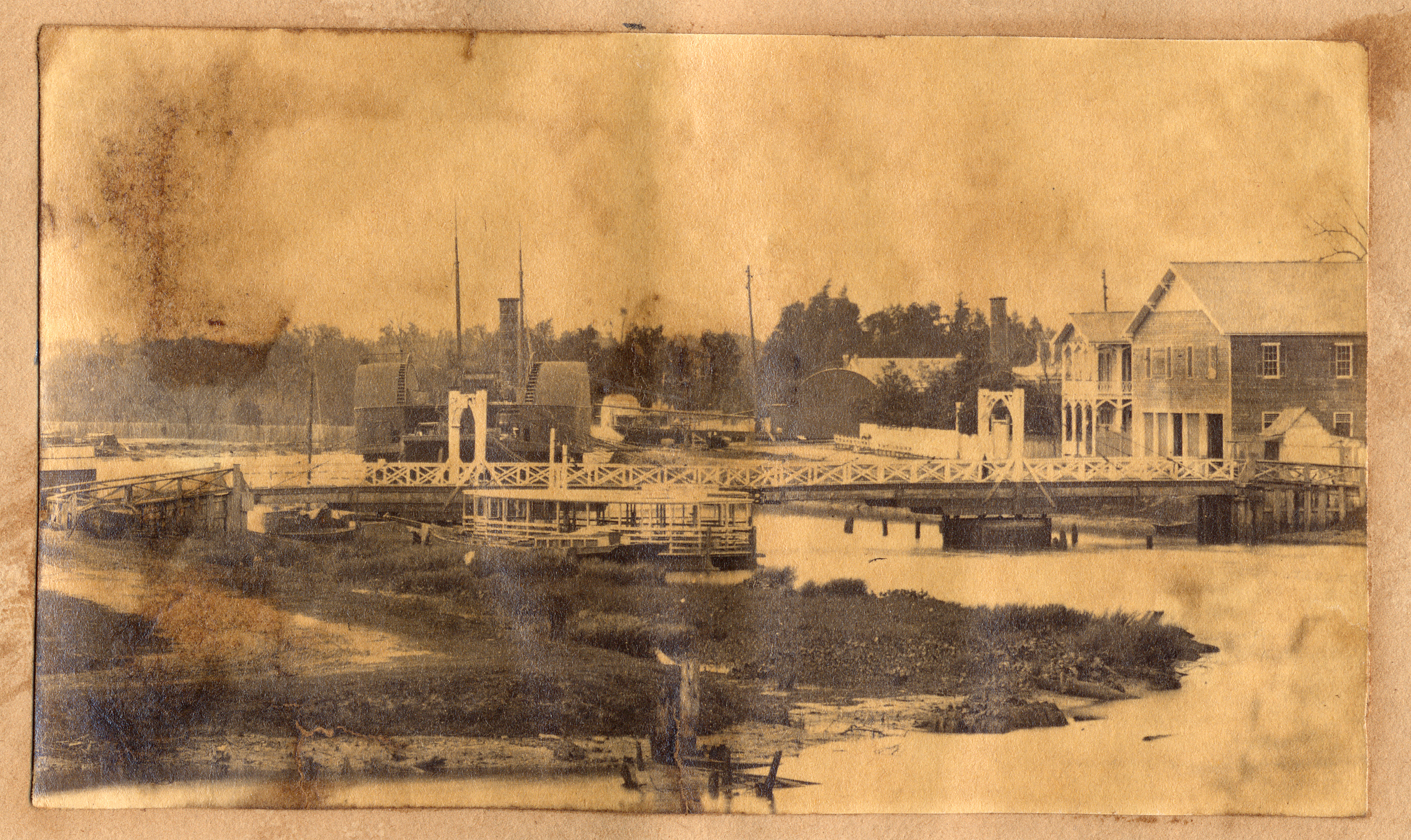

The following

images were taken by various New Orleans photographers and gives an idea of what

the Crescent City looked like at the time of the War Between the States.

St. Louis Cathedral

East bank Riverfront, Jackson Square

West bank Riverfront, Algiers shipyard

Camp Street

Decatur Street

Jackson Square

as seen from river

Waterfront, Jackson Square

Canal Street, looking towards the river

City Hall (left); Captain C. Slocomb's [5th

Company, Washington Artillery] house (right)

Bird's Eye view New Orleans skyline from St. Patrick's Church

Bird's Eye view New Orleans skyline overlooking Lafayette Square

Riverfront with steamships

Custom House under construction

St. Charles Hotel

United States Mint

Bayou St. John

Statue of Henry Clay at foot of Canal Street, looking toward St. Charles

hotel

Medical College of Louisiana on Common Street

Designed by architect James A. Darkin in 1847, it was the third largest in

the country.

A temporary arsenal for the Washington Artillery was across the street from

this facility after the Civil War.

.jpg)

Charity Hospital on

Common Street ( now Tulane Ave)

The building dates to

1832 and came under the administration of the Sisters of Charity,

who would partner with

the Medical College of Louisiana and run the hospital for the next century.

Gas Works, New Orleans

Christ Presbyterian Church, Canal St.

Canal Street

St. Patrick's Hall, New Orleans

Hotel Royal

Crescent City Billiard Club on right

General Benjamin Butler's Headquarters

Canal Street, looking from the river

Chalmette Battlefield

Steamboats on the riverfront

On the Waterfront

Cotton bales piled to the extreme!

HOME